This represents a significant advance on existing scanners that work in only two dimensions and are unable to identify many types of potentially dangerous items in passengers' baggage.

"It is a very exciting prospect in that we now have the best X-ray images that anyone has ever seen and the equipment is successfully tested and ready to be used at airports anywhere in the world," said Prof Max Robinson, the research team leader at Nottingham Trent University, English Midlands.

"I think one can justly compare the consequence of this breakthrough to that of the revolutionary replacement of black and white television colour. Today, nobody will consider monochrome viewing. It is going to be the same with X-rays. Without doubt in about a decade this is going to be the standard equipment not only in the area of security but equally in the medical and industrial inspection fields."

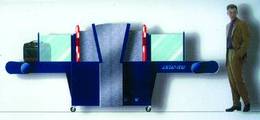

The Axis-3D

The airport machine was jointly funded by the United Kingdom and the United States governments. Called the Axis-3D the machine employs two X-ray beams instead of the one currently used in airport security channels. The second beam gives perspective to the image which can be rotated in order to see around the objects that are hidden or lying on top of each other.

The Home Office said the machine had already been successfully tested at London's Heathrow Airport. "This prototype has resounding implications for improving the speed and efficiency of security checks," said a spokesman.

Prof Robinson's connection with this specialised field goes back a long way. The UK security forces first called on his help in the '80s. Two police officers were killed in London during terrorist bomb disposal procedures and the force turned to Prof Robinson’s three-dimensional (3D) technology for possible protection.

Within six months he had given them a robot fitted with a 3D camera that could act as a human eye and help the police defuse bombs from a safe distance by using remote TV monitors.

Almost from the beginning the project was a great success and the technology's potential to save lives was firmly established. Its versatility has already become legendary. Since their introduction to bomb disposal duties the cameras have now been used on a huge robot to help decommission a chimney full of radioactive asbestos at a nuclear power station. Forensic scientists could soon be using the equipment in murder enquiries.

It was the terrorist bombing of a Pan Am aeroplane over Lockerbie, Scotland, in 1988, killing 258 people that served to revolutionise thinking about the way that X-ray machines were designed. But in fact Prof Robinson had been working on the problem long before that incident.

A complex problem

He says it is quite a complex problem. A two-dimensional photograph will offer the viewer enough information to make sense of what is being seen. But with an X-ray, because it is a flat image, it defies transmission to the brain of any notion of depth or perspective.

"If a normal X-ray is taken of two hands, one in front of the other, it is impossible to tell from that picture which is the hand in the foreground," explained Prof Robinson.

"They will be superimposed on top of each other. But a three-dimensional X-ray changes all that by allowing an operator to make sense of objects in a cluttered suitcase by seeing both behind and around them."

The technology is a world-first as nobody else has managed to successfully fire two X-rays at an object from different angles and then put the images back together again so they make sense to the human brain.

Prof Robinson achieved this seemingly impossible task by working out how to transpose the two images so they came together in exactly the same way that two eyes would put together a picture.

An elegant solution

His team came up with a very elegant solution to all the constraints imposed upon them. They used one X-ray source but created two beams that diverged from it. By controlling both the geometry and the precise time at which the visual information appeared they were able to reconstruct the image to obtain a picture as though the operative possessed 3D X-ray vision.

Quite early on, Prof Robinson realised the obvious approach of separate X-rays sources was impractical. This is because they would interfere with each other causing image degradation similar to 'snow' on TV screens.

Each X-ray has unique properties that would make it impossible to match in such matters as intensity fluctuations. With one source split into two beams all these constraints were overcome.

The 3D machine also gives a distinct psychological advantage. At the flick of a switch the operator can look either through the top or the bottom of the bag so avoiding viewing distant objects that are at the bottom of the bag so avoiding viewing distant objects that are at the bottom of a pile of other items.

As a result of the team's success a private company, Image ScanHoldings, bought the licence for the Axis-3D in 1996 and agreed to support Prof Robinson's research for the next five years.

The deal was worth £500 000 for Nottingham Trent University and marked the successful culmination of more than 20 years of research for the team.

The machine is now on sale and enquiries are already coming in from all around the world. The first unit has been bought by the US Federal Aviation Administration.

Looking to the future the team has already been approached by the MedLink organisation to look into the feasibility of a 3D machine for breast cancer screening.

Another important potential market sector is in the inspection of electronic assemblies. Today, a lot of the contacts are positioned underneath the component itself making visible light inspection almost impossible.

To overcome this, Robinson is already far advanced into a proposal to build an industrial version of this machine.

For details contact Prof Max Robinson, Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, Nottingham Trent University, tel: (0944) 115 948 6491; fax: (0944) 115 948 6567, or e-mail: [email protected]

© Technews Publishing (Pty) Ltd. | All Rights Reserved.