The image of security has changed fairly radically in recent years, but at times is still associated with a fairly abrupt and unhelpful encounter with an unhelpful person.

In cases like this, the security official is seen as an obstacle rather than as someone who is facilitating a situation. At times this barrier function may be a necessary approach, however, the challenge for security is to move to being a resource through a client-centred approach. This is likely to gain a great deal more credibility with people.

While this shift is increasingly being recognised by security companies who are emphasising how their officials come across, the extent to which it is done often defines how security workers are recognised and appreciated with clients. The interface between the employees, who are often guards and operators, and the client will usually determine how the company is perceived and its competitive edge in the business. From how the company management generates an image at an executive level to how officials at the interface actually deal with clients all lead to a security climate. The more consistent this is, the stronger the climate formation.

Creating the balance

Creating a security climate is not a one-way process. Dr David Holman, a psychologist, draws an analogy between creating a safety climate and a security climate. The more clients feel value and get along with security, the better they respond and the more a positive relationship can develop.

Where security officials get ongoing positive feedback and reinforcement, they will tend to thrive on this and do it more, with the feedback loop reinforcing this continually over time. Where security officials are seen as bureaucratic and obstructionist, the more people will treat them in a negative and confrontational manner.

The effectiveness of security officials is influenced by their internal feelings, values and coping strategies, as well as how interpersonal dealings affect people. Holman discusses how affect regulation can be used to improve the way that a person can come across to others. The approach is also being used in call centres to adjust the orientation of personnel to the nature of the work that they do.

Holman describes how people can change through surface acting, or deep acting. In a situation where a person is using surface acting, the security official may make a conscious attempt to try and be polite and responsive within a difficult situation despite feelings to the contrary. In deep acting - it involves changing emotions and feelings so that the person feels differently about the situation that they need to deal with.

If, for instance, security officials feel they are making a contribution to facilitating total service delivery, they will act and feel very differently than if they are merely there as an unpopular function. Similarly, if management sees it the same way, this has to rub off on security.

Acting analysed

Surface acting tends not to be as meaningful - it tends to be more easily identified because of inconsistencies in how the person comes across. Put simply, the person's heart is not in the activity and sometimes this can show up in less genuine body language. Greater fatigue is generated by having to do surface acting - smiling and being polite while really annoyed with the person. The acting generates some pressure and stress. If continually repeated, it both tires the person out and creates a short fuse that people are likely to lose their temper more easily.

Deep acting aligns the person's commitment and emotions to the task they are doing and helps people work through far more difficult situations than otherwise may be the case. It also gives people more emotional resilience and patience.

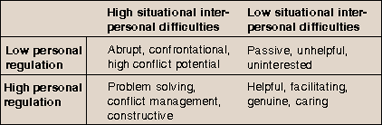

Table 1 shows some of the implications of situations where personal regulation types are combined with the difficulty of situations.

The capacity to have strong personal regulation varies according to people, and some have this more than others. Ideally one should get this at the recruitment stage. However, according to Holman, it is also possible to develop this through training. Practising techniques that assist rather than detract from effective emotional regulation is also important. For example, some activities that create a problem-solving environment as opposed to a confrontation environment can include:

* Be receptive and friendly to people.

* Use active listening.

* Ensure you understand the request or problem.

* Reflect back to confirm the issue.

* Explain the context.

* Continually inform people what is going on.

* Suggest alternatives.

* Assist where possible.

* Reassure people.

The end result

These activities would all help in creating a shift to a more client-orientated security climate, whether done from gate guards or a sophisticated control room. The focus moves from just ensuring compliance to active participation. Along with this is a need to reinforce such activities with recognition and rewards to promote and value the behaviour, and to promote positive feedback.

Social support from managers is important in this process, as is training. You find that a natural orientation for helping behaviour and a desire to do well will not only differentiate good people, but also produce great companies to work with.

Dr Craig Donald is a human factors specialist in security and CCTV. He is a director of Leaderware, which provides instruments for the selection of CCTV operators, X-ray screeners and other security personnel in major operations around the world. He also runs CCTV Surveillance Skills and Body Language, and Advanced Surveillance Body Language courses for CCTV operators, supervisors and managers internationally, and consults on CCTV management. He can be contacted on +27 (0)11 787 7811 or [email protected]

| Tel: | +27 11 787 7811 |

| Email: | [email protected] |

| www: | www.leaderware.com |

| Articles: | More information and articles about Leaderware |

© Technews Publishing (Pty) Ltd. | All Rights Reserved.